Black Montana is a story that has yet to be told in history books. It is a significant puzzle in unlocking the African American experience, yet so little information is known. You’d think that it would be a popular area of study however efforts to unravel this hidden narrative have only begun recently. Black Montana is historically one of the best attempts at picking up scraps and pieces of a full story. Anthony W. Wood has taken it upon himself to delve into uncharted territories and synthesize the African American experience of the Northeastern Rockies. Black Montana is a book created almost entirely through Wood’s contributions to the Archive of Montana. Wood cleverly used Montana’s century-old census to create a comprehensive map of Montana and analyze its developments. With the aid of multiple secondary sources, Wood has achieved something unprecedented.

On this website, I will reiterate some of the major points made throughout Wood’s narrative of the experience of Black Montanans as well as provide a rhetorical analysis of Black Montana

The Golden West

Wood makes a point to express how white people weren’t the only ones motivated by the new opportunities moving westward. He expands on how after the Civil War, it was difficult for African Americans to become self-efficient in a world built around their exploitation. Wood briefly reviews how many African Americans before the turn 20th century had to return to their previous slave masters and participate in one of the few methods of self-sustainment, sharecropping. Sharecropping was a system where landlords allowed ex-slaves to use their plantation land under careful supervision and promise of a typically large share of profits. In other words, sharecropping is most famously dubbed “slavery by another name”

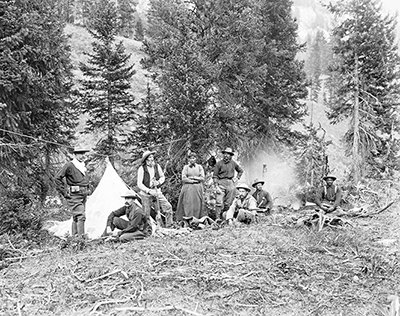

Instead of settling for another oppressive system, a very small handful of African Americans decided to journey westwards. This at the time is one of the most dangerous journeys to make as much of the west is considered uncharted territory. Nevertheless, these African Americans would join the White people expanding westward in colonizing Native American land. They unhesitantly capitalized on the land taken from Native Americans in order to secure the emerging Black bourgeoise class. From here African American settlers began to consolidate their own ethnic colonies within Montana, however to two most influential populations of Black settlers are located in Helena and Butte, Montana

Securing Black Settler Space

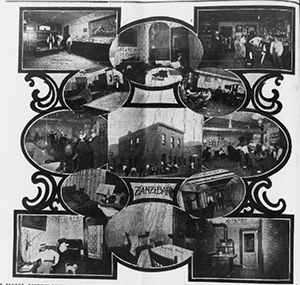

Black Settlers slowly began to make a comfortable life for themselves within their colonies, they established their own newspaper such as the Colored Citizen in Helena. Eventually had full and unseparated access to equal education facilities well into Jim Crow and, most notably created a black-owned club called Zanzibar, named after the African territory.

The Zanzibar cultivated a sense of place for the Black community. The club was a physical location where being Black and being a Montanan were one and the same. A powerful image of African American identity was uncovered by Anthony Wood’s research.

African American Wilderness Conservationism

Finally, I believe a major aspect of Wood’s narrative is the major contributions Black Montanans made toward preserving and maintaining wildlife. There was a crisis emerging within Montana where sheep were being inflicted with cuts and gashes. The culprit was pinpointed to be the indigenous “Magpie”, yet African Americans were also being blamed for the status of the sheep. African Americans then had to turn to members of their own community to preserve the wilderness as well as create a general connection between humans and Nature.

Analysis of Wood’s Compelling Rhetoric.

Black Montana, although a narrative of the African American experience of 1877-1930, is arranged thematically rather than chronologically. Therefore the themes the book explores, or rather the chapters separating the book are black settler colonialism, the creation of black settler space, the “Negro question”, black wilderness conservationism, miscegenation, and the racial erosion of Montana. With this clear separation of topics instead of a cohesive, and to many readers rather boring retelling of events, Wood is able to maintain reader engagement. In each chapter, the reader learns an impressive fact about Black Montana and with it, a certain feeling of empathy. For example, within Chapter 3, Great Debates, the reader may be surprised to learn that Butte, Montana was home to one of the world’s most profitable companies(Wood, 115). However, the sheer fact posed a major vacuum to focus on Black Montana; especially after the founder, Marcus Daly’s death. At the beginning of the chapter the reader also learns how before attention was driven away from Black Montana, it was home to a community of “progressive” African American families as early as the turn of the 20th century(Wood 105). This feat was so impressive that it shocked Booker T Washington and W.E.B DuBois themselves.

In order to deliver the vast amount of information in such an engaging way, Anthony W. Wood consistently foreshadows what is to come, also flashbacking on points made in the past. This not only keeps the reader engaged but also aids their retention as previous points are stressed. Throughout the chapters, Wood starts some sentences by stating “This chapter focuses”, “This chapter will demonstrate” and even “the next chapter seeks to”. This rhetorical strategy forces the reader to be engaged as it automatically makes the reader anticipate what is to come and involuntarily forces them to ask questions about what is to come, in other words, “food for thought”.

In addition, at the beginning of each chapter, Anthony W. Wood starts the chapter with somebody’s personal account. He does this because somewhere within the story a major detail appears which allows him to segway into the rest of the chapter. For example, at the beginning of Chapter 4: Thinking with Magpies; Wood introduces a biologist named Sherlin Stillman Berry who is investigating why so many sheep in the area have scars and cuts. When it is found that the reason behind the scars is due to a bird species called Magpies and Berry expresses his disgust in such an “unwanted” species, Wood brilliantly shifts to developing an argument that this thought process behind Magpies reflects how white settler colonists view indigenous people(137-138).